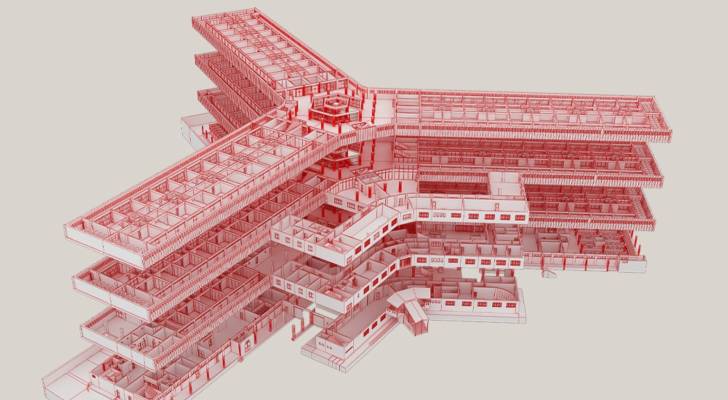

Blueprint of Sednaya prison (Credit: Syria Prisons Museum)

Syria launches virtual museum documenting decades of prison abuses under Assad

A Syrian organisation unveiled a virtual museum on Monday that chronicles the experiences of detainees in the country’s prisons, long used to suppress opponents of the Assad family.

The Syria Prisons Museum offers 3D virtual tours of detention facilities, firsthand testimonies from former prisoners, and extensive research, studies, and investigative reports about Syria’s prison system.

“The museum seeks to preserve the dark Syrian memory associated with violence, murder, and prisons,” said Amer Matar, the project’s founder, speaking to Agence France-Presse (AFP) at the launch event held at Damascus’ national museum.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, more than two million Syrians have been imprisoned under Assad family rule, which lasted over five decades until Bashar al-Assad’s ouster in December. Half of these detentions occurred in the aftermath of the 2011 protests, when peaceful demonstrations were violently suppressed, triggering the 14-year civil war.

The Observatory estimates that over 200,000 people have died in Syrian prisons, many executed or tortured. Sednaya prison, in particular, was described as a “human slaughterhouse” by Amnesty International.

The Prisons Museum Foundation, which spearheaded the project, based its methodology on work conducted in 2017 documenting conditions in Daesh detention centers. Following Assad’s removal, the organization collaborated with Syrian and international groups specializing in missing persons and criminal justice to build the virtual museum.

The initiative combines field documentation, survivor testimonies, interviews with families of missing persons, and a digital archive reconstructing prison interiors.

“We were afraid that these prisons would be destroyed before we could document them, but to date we have been able to enter 70 prisons,” Matar said.

Organisers say the museum aims to honour victims, amplify survivors’ voices, and compile evidence for future accountability. “We are trying to build a living digital archive,” Matar added.

Throughout Assad’s rule, prisons were used as instruments of fear and repression. Many detainees never returned, and even after the regime fell, the fate of numerous prisoners remains unknown.

In May, Syria’s new authorities announced the formation of a national commission for missing persons and another for transitional justice. While rights groups welcomed the initiative, they warned that achieving justice will be a long process, calling for independent investigations and accountability for all parties involved in the conflict.